I had a creative writing professor who, when asked what poetry was, replied that it was playing with white space on the page. My linguisticky soul, to be sure, was rather indignant at this. Well I never! The void on a page, indeed! What about sibilant syllables furtively whistling, while fricatives follow in their footsteps behind? Of course, after I had designed some fantasy orthographies of my own, I came to see that he had a point about the importance of the graphical element in language. Spoken language and writing go together hand-in-glove, the structure of one imposing strict limits on the form of the other. But I still think that that definition might be a bit too restrictive. After all, poetry is also music--playing with sounds. These two simple insights taken together suggest a new definition for poetry--poetry is language-play.

A certain amount of poetical, playful thinking is useful to the conglanger, whose business it is to mess with the building blocks of language. In the previous article we saw that even children as young as 4 years old can deploy English patterns in xenowords they had never heard before. In this article we will investigate three examples of fully mature language-play that push English’s patterns to their limits

We will look at Lewis Carrol’s The Jabberwocky; Paul Eluard’s The Earth is Blue as an Orange; and Paul Andersson’s Uncleftish Beholding. Carrol’s poem delights in the production of xenowords, spilling out sweet-sounding nonsense in great profusion. Eluard, in dream-like, surreal style, shows the limits of the dictionary, swelling ordinary words to bursting with excessive meanings. Andersson invents an imaginary time machine, and gets lost in an alternate timeline where English was never influenced by French or Latin.

The Jabberwocky

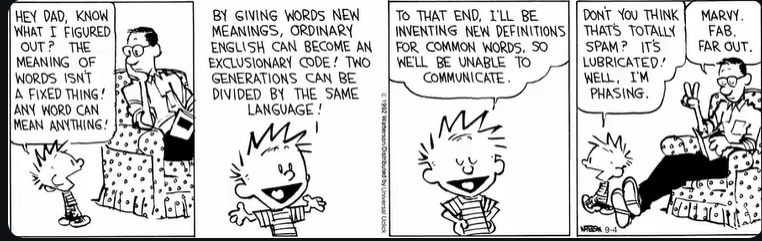

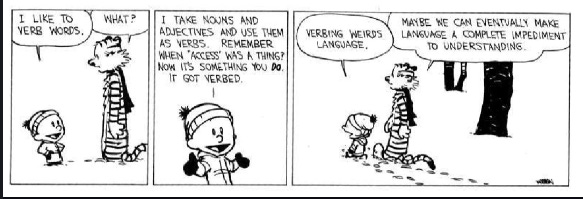

In the dream-world behind the looking glass, words are living things with their own lives, personalities, and--apparently--jobs. Humpty Dumpty employs them, whose force of will is enough to whip any word into shape “When I use a word,” Humpty Dumpty tells Alice, “it means just what I choose it to mean—neither more nor less...they’ve a temper, some of them—particularly verbs, they’re the proudest—adjectives you can do anything with, but not verbs...” Humpty Dumpty goes along to demonstrate this mastery by giving totally off-the-cuff meanings to impenetrability (which means “I’ve had enough of this subject”) and glory, which is apparently a “knock-down argument.”

As annoying as the ovoid gentleman might be, he does have an interesting insight about what happens to words when you take away their meanings, or at least about what happens when words’ meanings are so fluid as to be changeable at a whim.. As we saw in the previous article, children are able to deploy the correct plural for xenowords they have never heard before. That is to say, they were able to fit the “words” into grammatical and phonological patterns, despite them not having any real-world referents.

When you take a word’s meaning away, what remains is the word’s membership to a language-pattern. The nature of an individual word’s membership to a language-pattern determines that word’s part-of-speech. This gives us some further clues about how xenowords work, how they are able to slip surreptitiously into proper-sounding sentences. Xenowords are able to pass as real words, not only by virtue of sounding like them (phonological-camouflage) but also by virtue of patterning like them (grammatical-camouflage)

Now, you probably remember parts of speech from elementary school. I remember them too. They were, after all, drilled assiduously into my head: “a noun is a person, place, thing, or idea; a verb is an action or state of being; an adjective describes a noun; a preposition describes a location, direction, or orientation...” and so on and so forth in any number of variations. This is a semantic definition of part of speech. You’ll notice straight away that it contains an appeal to the meanings of the words in question. A noun is a noun if its meaning is one of four things. A verb is a verb if its meaning is active or stative.

Humpty Dumpty, unfortunately, scoffs at such simplistic definitions. To him, a word means whatever the scornful ovoid conlanger says it means! Does the Oxford English dictionary list impenetrable as an adjective? Too bad! The not-egg declares that it shall be a whole-ass sentence! And what about words that aren’t in any dictionary but the dream-dictionary? What about the strange and seductive xenowords that compose the first stanza of The Jabberwocky?

’Twas brillig, and the slithy toves Did gyre and gimble in the wabe: All mimsy were the borogoves, And the mome raths outgrabe.

How in the hells are you going to be able to figure out the part-of-speech of these audacious utterances? Let’s play a game. Tell me, dear reader, if you have not been bewildered like poor Alice, what would be your best guess at the parts of speech of

brilig,

slithy,

toves,

gyre,

gimble,

wabe,

mimsy,

borogroves,

mome raths,

outgrabe?

Admittedly, you don’t have meaning to help you out. You can’t know whether slithy is a descriptive word or a word for a person, place or thing, just by looking it up in the dictionary (I know later in the novel, Humpty Dumpty gives interpretations of these words, but let’s just use the text for now) However, you wouldn’t be completely in the dark. You see, by relying on your knowledge of patterns as they apply to regular, dictionary-words, you can extrapolate a xenoword’s part of speech, by observing what pattern it correlates with. To show you what I mean, I’m going to give the parts-of-speech for all the above xenowords, and explain how I got to that conclusion.

So to begin:

Brilig

This is a tricky one. It’s part of the phrase ‘Twas brilig..., which the word ‘twas is a fancy contraction of it was. So we gotta ask ourselves, what kinds of words tend to appear after it was? Well, there’s lots of different kinds of words or phrases that can come after it was, e.g. “it was raining; it was a bad day; it was loud; it was evening; it was an elephant...” and so on and so forth. We will have to look more broadly at the poem to glean information about briling. The formulation ‘twas brilig has about it a certain smack of “once upon a time.” It sets a scene by invoking a mood. The lines after this opening line seem to be generally descriptive in character, painting a dream-portrait of surreal creatures doing weird things. Perhaps this opening phrase could be a kind of invocation to strangeness? A kind of setting of the mood? It’s a vague little word, but it works wonders.

Slithy

This word, like mimsy which appears in the third line, seems to be a composite of slithe and -y. The -y suffix here would suggest that slithy is an adjective, after the pattern of real words like, creep-y, scar-y.

Toves

Toves is part of the phrase the slithy toves. The internal composition of toves suggests that it has been declined for plurality. That is to say the -s ending is suggestive. Only nouns may receive a plural suffix, therefore toves, which seems to have a plural suffix, is a noun. Its identity as a noun is further confirmed by its co-occurance with slithy, an adjective. Adjectives co-occur with nouns or with other adjectives. Toves co-occurs with slithy, so it’s either an adjective or a noun. It’s not an adjective because it receives plural markings (the -s ending), therefore, it’s a noun

Gyre

Is found in the phrase did gyre and gimble in the wabe... The function word did only precedes a verb, as can be seen from the unacceptability of phrases where it precedes other elements, e.g.. *did rumination and driver in the wabe (the asterisk indicates an unacceptable phrase). The co-occurance of gyre with did suggests that gyre is a verb.

Gimble

Is in a conjoined phrase with gyre, i.e., did gyre and gimble. Only elements belonging to the same grammatical pattern can be conjoined with an element such as and, or or, as can be seen from unacceptability of sentences where disparate grammatical categories are conjoined, e.g., *The witch rode and the broom; *the pumpkin grew and orange. It seems likely therefore that gimble is a verb like gyre.

Wabe

It occurs in a prepositional phrase, in the wabe.. Prepositional phrases can only take noun phrases as objects, e.g. in a moment, on the wall, as can be seen from the unacceptability of phrases where they take verbs of adjectives: *in a blue, *on the suspend. This suggests that Wabe is a noun.

Mimsy

The internal shape of this word is suggestive. Intuitively, I am immediately driven to decompose it into a root and a suffix, i.e., mims- and -y, and assign it a status as an adjective This is because the -y suffix in English is very productive at making adjectives. We have a bunch of examples: fishy from fish; witchy from witch; tricky from trick and so on. The -y suffix has a meaning that could be summarized as “transform root noun into adjective meaning having the qualities of the root.” Generalizing on the pattern, we could conclude that mimsy is an adjective derived from an imaginary noun root, mims-.

Borogroves

This word is a noun. It occurs after the which can only take a noun or noun phrase as a complement, e.g. the large pink elephant vs. * the large pink gaseous. Furthermore, borogroves takes a plural morpheme, as only nouns can.

And the mome raths outgrabe

I’m addressing these xenowords as they appear together in their final line because the interpretation of the one depends on and influences the interpretation of the others. So when looking for these words’ parts-of-speech, we’ve got several options. For one thing, we could assume the mome raths outgrabe is a standard English subject-verb-object sentence, on a similar pattern as The goblin loves butter, where mome-- like, the goblin-- is the singular subject; rath-s--like love-s--is a verb conjugated in the third person; and outgrabe is an object-- like butter--the recipient of whatever the hell rathing is.

But that’s not the only option. You would also be justified in reading raths as a plural noun. If you adopted that reading, then mome would have to be an adjective of some kind, or maybe another noun. Maybe mome raths is a compound of two nouns like Foot path or butter knife. If that were the case, then what’s outgrabe? Outgrabe seems to be composed of a preposition, out, and a root, grabe, whatever that is. It recalls reals words like outside, outdoors, downriver. Adopting this pattern, outgrabe would be a special kind of preposition referring to the spatial orientation of the mome raths--there’s too many options!

So, with every possible path in the semantic wilderness stretching before us, we turn to Humpty Dumpty for enlightenment, who informs us that outgribbing is a verb! “Something between bellowing and whistling with kind of a sneeze in the middle.” Humpty Dumpty is a prototypical conlanger. For him words are naught but sound and structure, waiting to be filled with meaning. Being able to conceive of languages at an abstracted, extra-meaningful level is a vital skill for the conlanger, or for anyone deeply studying languages for that matter. It is a useful skill because it helps break you out of the habit of thinking that there’s only one way for any language to talk about something. For any one situation happening in the world, there’s dozens of different way to linguistically encode it. The task of the conlanger is to find novel ways to capture relevant aspects of a situation in their language.

The Earth is as Blue as an Orange

I have translated Paul Eluard’s poem from French into English, adhering as closely as possible to the surreal semantic paradoxes that it showcases. The Jabberwocky makes xenowords by sticking to established grammatical patterns. Eluard’s poem weirds the grammatical pattern itself by placing real words in strange relationships to each other. Here is the poem below.

The earth is as blue as an orange

Never an error, words do not lie

They give you nothing more to sing

Time for the kisses to be heard

Madmen and lovers

She has her mouth of alliance

And such garments of indulgence

As to appear fully nude

The wasps verdantly bloom

And the earth puts around her throat

A necklace of windows

Thou hast all the solar joys

All the sunshine in the world

On the pathways of thy beauty

If this poem sounds strange in English, don’t worry: It’s even weirder in French. Right from the get-go, we have a lovely color paradox: the earth is as blue as an orange. This, to be sure, sounds like a perfectly fine sentence. We know the meaning and usage of each individual word in this sentence, in a way that we didn’t for the words in the Jabberwocky; and yet....something doesn’t quite add up. An orange isn’t blue, and the earth, which is somewhat greenish-blue, certainly doesn’t resemble an orange in color. There’s a mismatch in the comparison. The abstracted pattern used here is: X is as Y as Z. In ordinary speech this pattern works fine, e.g. I’m as happy as a lark; it’s hot as hades! But poetry is, famously, not ordinary speech. Poetry is language-play, as you recall; and Eluard is playing with this pattern like a child in a toystore.

As you may remember from previous articles, one can define language in one of two ways: 1) as a mathematical-logical system for taking small bits and combining them into larger bits according to precise rules; and 2) as a socially-bound communication system full of conventions, culture and history. Eluard and Carol were interested in this first way of looking at language, at least in these poems. In French, as in English, the basic word-order is

Subject-Verb-object

(of course, it should be mentioned that French has a lot of sentences where the word order is shifted around, sometimes for grammatical reasons, sometimes for discourse reasons, but this generalization will do for now)

Now, the thing to notice about the abstracted representation of word-order, is that the terms subject, object, verb name entire classes of entities. That is to say, that you theoretically could put any word into the subject position (so long as it was a noun-phrase); any verb into the verb position; any object into the object position--and they would remain subjects, objects, and verbs, solely by virtue of their positional relationship to each other. And not only that, but the sentence would theoretically be grammatically correct, even if its meaning was not transparent from its parts. And that leads us nicely to the second line: “Never an error; words do not lie.”

Indeed, words do not. In this particular poem, it is the very structure of the sentences that is deceptive, or at least indistinct. However, we must not get caught up thinking strictly in terms of sentences, because, after all sentences themselves are composite, made up of several phrases. The poem uses loose phrases and to evoke a sort of semantic-soup, as it continues.

“They give you nothing more to sing

Time for the kisses to be heard

Madmen and Lovers

She has her mouth of alliance

And such garments of indulgence

As to appear fully nude”

The appearance of the conjoined nouns madmen and lovers, just floating in the middle of the poem, not attached to a phrase before or after it, does kinda remind me of impressionistic music, how it sets a mood without really fitting into a larger pattern. Who are the madmen and lovers? What is their connection to the female-person with the “garments of indulgence?” It is not clear. Nor is it supposed to be. Structure in this poem is nothing but an excuse for Eluard to juxtapose unusual objects and make impossible comparisons. The structure is not what is important here, but rather the combinations of vocabulary items that it permits.

The Concluding lines of the poem evoke a strange cheerfulness and awe

“The wasps verdantly bloom

And the earth puts around her throat

A necklace of windows

Thou hast all the solar joys

All the sunshine in the world

On the pathways of thy beauty”

Even though I couldn’t tell you what exactly the earth putting a necklace of windows around her throat would look like, I could tell you that it sounds like a beautiful thing. I mean, the earth wearing a necklace is evocative and strange; and a necklace made...of windows?! Well, I never! And where would the throat of the earth be? Wherever it is, all the solar joys, are on the pathways of her beauty, some of which may lead to her throat. Surreal imagery and fuzzy syntax.

Now, if it seemed to you that I was being a literalizing square in my reading of the poem, deliberately insisting on reading it at face value, and callously eschewing a metaphorical reading, you would not be mistaken. I did it on purpose! to prove my point about poetry being language-play. You see, a literal reading of poetry really struggles to deal with the playful attitude towards language that poetry embodies. Taking language seriously--that is, literally--makes linguistic creativity into just a means of efficient communication. Not to knock efficient communication, of course--but poetry is interested not in communication primarily but rather in evocation.

Even the words of the diction’ry,

Whose senses are already decided,

Get new connotations and new implications,

When in poems they are combinèd.

Uncleftish Beholding

This last example of language play is the closest to world-building conlanging of the examples we have investigated. The article Uncleftish Beholding is a two-page resume of atomic theory, such as one might find in a high-school freshman’s physics textbook. And yet, there is not a textbook in any school in this reality that introduces atomic theory like this

For most of its being, mankind did not know what things are made of, but could only guess. With the growth of worldken, we began to learn, and today we have a beholding of stuff and work that watching bears out, both in the workstead and in daily life.

Were you able to figure out what was being said? To me it sounded kinda familiar, kinda arcane, kinda like how sea-faring dwarves might speak in a fantasy world. The xenowords here--worldken, beholding--have a distinctly olde feeling about them. One reason for this perception might have to do with the design parameters of Uncleftish Beholding. Paul Andersson wanted to see what an English from an alternate timeline would look like, a timeline where there had never occurred the Norman invasion of 1066, which had imported an immense amount of French and Latinate vocabulary into English. In this timeline, English’s vocabulary is derived entirely from words of Germanic origin. There aren’t any Greek “inkhorn” words either. If the Germanic words feel old, then that may be because French and Latin words in English feel new. I’m not going to quote the entire article, but the next bit is well worth reproducing.

“The firststuffs have their being as motes called unclefts. These are mightly small; one seedweight of waterstuff holds a tale of them like unto two followed by twenty-two naughts. Most unclefts link together to make what are called bulkbits. Thus, the waterstuff bulkbit bestands of two waterstuff unclefts, the sourstuff bulkbit of two sourstuff unclefts, and so on. (Some kinds, such as sunstuff, keep alone; others, such as iron, cling together in ices when in the fast standing; and there are yet more yokeways.) When unlike clefts link in a bulkbit, they make bindings. Thus, water is a binding of two waterstuff unclefts with one sourstuff uncleft, while a bulkbit of one of the forestuffs making up flesh may have a thousand thousand or more unclefts of these two firststuffs together with coalstuff and chokestuff.”

The level of word-play here is simply astonishing. What Andersson did was take the etymology of the standard scientific terms, derived from Greek and Latin, and reproduce that etymology using equivalent words of Germanic origin. So, for instance, take the word firststuffs. This is the word for element. The word element comes from the Latin elementum, which referred to a basic or fundamental thing. So the idea of basicness and fundamentalness is captured by the word first-, in the compound, firststuff. And stuff is…just stuff. Bulding blocks of matter. Let’s go on. Motes are particles. Unclefts are atoms, with the idea of indivisibility being present in the etymology of both terms, atom, coming from the Greek word for an uncut thing. A bulkbit is a molecule; and I bet that you can immediately guess that waterstuff is hydrogen. Indeed, Wasserstoff is hydrogen in German. Sourstuff, from German sauerstoff is oxygen. Coalstuff and Chokestuff are carbon and nitrogen respectively, related to the German Stickstoff and Kohlenstoff.

Uncleftish Beholding features a speculative conlanging, from a historical perspective. Like The Jabberwocky and The Earth is as Blue as an Orange, it’s interested in the slipperiness of words’ meaning, and in how easy it is to make new ones.

Andersson highlights the connection between a word’s history, its form, and its meaning. You’ll notice that whenever he makes a xenoword, it’s always a compound? That grammatical choice is very deliberate. Highly productive word-compounding is a characteristic of the Germanic languages, one that they do not share with the romance languages, whose word-building mechanisms are more restrained. Why do Germanic languages prefer compounding? Call it a historical consistency, the preservation of a prominent old linguistic pattern across generations. As with any other tradition, the most prominent parts of a language are the ones most likely to be retained.

And the choice of words, too, was very deliberate. Andersson took care to excise even very commonly used words in favor of a Germanic equivalent, even where the Germanic word sounds kinda awkward, e.g. saying “mankind” instead of “humanity;” and “ watching bears out” instead of “observation bears out.” The overall aesthetic effect of such substitutions is one of cozy strangeness. “Waterstuff” sounds less abstract, more tangible than “hydrogen.” “Chokestuff” sounds like it might actually kill you, whereas “carbon” evokes “carbon-copy” and safe sameness. One wonders what other substitutions this alternate-English might make.

Whoof! That was a lot more difficult than I anticipated. I would like to thank my readers for offering me encouraging advice when I reached out complaining of writer’s block, because boy-howdy did this article ever kick my ass. But it’s finished now, and I do hope that y’all may derive some inspiration and ideas from them. Until next time!

fascinating, all of it. glad you powered through!