I recently discovered a lovely little show on Disney, called The Owl House. I don’t think I’d be doing Dana Terrace any disservice by characterizing her creation as a curious admixture of Alice in Wonderland, Adventure Time, and Hieronymus Bosch. Indeed, Terrace herself credits Bosch’s surrealism as a major inspiration for the show’s imagery

(https://www.newsweek.com/owl-house-creators-talk-bringing-creepy-back-disney-dash-bosch-1481110)

Yet the whimsically infernal illustrations and cartoon nonsense were not the only things about this show that captured my imagination. In the second episode of the second season, I came across an exposition of glyph magic that made me start up in my seat and spew out my proverbial cornflakes. Luz, the plucky human protagonist had just described glyph magic as syntax!

As a human trapped on the Boiling Isles--where magic is real and myth commonplace--Luz is unable to instinctively cast magic like other witches. The mere intent to cast a spell is insufficient. This disadvantage leads her to discover the ancient secret basis of Magic: wild magic, expressed in glyphs. By inscribing the proper glyph onto a sheet of paper, she is able to “spell” blinding light, or pillars of ice, or thick vegetation into existence. In this episode, Eda, the short-tempered witch with silver hair, has lost her powers, and is working together with her stickler sister to re-acquire them.

So, before we dive into a nerdy explanation of how this glyph system corresponds in to real-world languages’ syntax, we have to talk a bit about what Syntax is in a Language and what it does.

Syntax is basically the ability of language to express different meanings by modifying the arrangement of words. When you study syntax you try to characterize these arrangements in terms of speakers’ underlying awareness of linguistic patterns. The fundamental way in which this awareness is characterized is compositionality. The basic observation about languages is that they yoke words together to compose sentences.

The yoking metaphor is particularly apt here. You can imagine words like different kinds of working-animals: you’ve got your noun-bulls over here; and your verbal horses across the field; and a team of adjectival huskies ready to pull a sled up the mountain. Diverse yoking apparati are going to be required to harness the collective power of each these different animal assemblages. A thick, broad yoke for the bulls; a long slender one for the horses; leather straps and ropes for the dogs.

In talking about the compositionality of language, linguists distinguish between words and phrases. Words are like the living animals. Full of power and potential. Existing on their own as the essential foundation of linguistic labour, clothed in nothing but their own meaning. Phrases are like the various yokes that bind them together so they can do stuff for humans. A solid, weighty noun-phrase yoke for the bovine words; a slender verbal-yoke for the equine verbs; a flexible and adaptable one for the canine adjectivals. The cool thing about languages is that they don’t just yoke animal-words together: the main compositional strength of language is its ability to yoke yokes to other yokes, if that makes sense. If not, let’s go over some examples before we disappear too far up the ass of abstraction. Take the following phrases.

The grimoire

The scarlet grimoire

*The scarlet

The seductively scarlet grimoire

*The seductively grimoire

So let’s see what can be seen. In example (a) we have “the” combining with “grimoire.”

Now what kind of animals are these words--what’s their part of speech? We have “grimoire,” a noun; and “the,” a determiner. So let’s stay with the metaphor of yoking, and see how far we can go with it. It would seem from this initial observation that nouns and determiners get comfortably yoked together. Let’s show them joined with a single graphic.

The D and N stand for determiner and noun respectively. I’d say this is a happy little yoking. Pretty uncontroversial to say that determiners combine with nouns. We don’t have a name for the type of combination they enjoy....yet, but I have no doubt that we’ll get there as we examine more examples. Let’s see what else determiners combine with in examples (b) and (c). From example (b) it looks like the D combines freely with nouns and adjectives (if you’ll pardon my French), and we could show their tripartite linkage like so:

Except....that (c) is totally weird. You’re left asking “the scarlet what?” So the yoking of just a determiner and just an adjective doesn’t happen.

Buuuuut, adjectives will yoke with nouns, as you can see.

So, if a phrase like “the scarlet grimoire” is going to make sense (and it does) then that means that the “the” doesn’t combine with the adjective but with the whole-ass noun-adjective combination. A yoking between a word and another yoking of words. It would look like this.

This simple little collection of yokes adequately captures English speakers’ intuitions about the compositionality of phrases. We are almost in a position to give the yokes names, but not quite. We need first to draw yokes for sentences (d) and (e). Except…there’s a problem.

The problem is that in (d), “the seductively scarlet grimoire” we might be justified to say that the adverb “seductively” combines with the noun just like the adjective does. Only...that’s not the case, because (e) “the seductively grimoire” is nonsense. We need to account for the fact that a determiner can yoke with a noun, with a noun-adjective combo, and even with an adverb-adjective-noun combo and for the fact that it can’t yoke with just an adjective or just an adverb.

To explain how even a simple bit of language like “the seductively red grimoire” gets its meaning, we need to realize that words come prebuilt belonging to a phrase.

When words combine, they do it at the phrasal level. Just as an oxen yoke is particularly suited to the frame of an ox, so too does each word project a phrase suited to its grammatical class. So nouns belong to Noun phrases; adjectives to adjective phrases; determiners to determiner phrases and so on. When words combine, they combine at the phrasal level. Without the yoking structure of the phrases, words would be unable to link up in any meaningful way. Think about it. You intuitively know that “scarlet” modifies grimoire, that “seductively” modifies “scarlet” and that “the” modifies the whole assemblage. As an English speaker, these jots on the page have meaning and coherence to you. If English wasn’t you native language “the seductively scarlet grimoire” would be just as meaningful as “grimoire the seduc-scarlet-ive”! And this would be not only because you wouldn’t recognize the any of the words, but also because you’d have no idea what order they were supposed to be in. The full structural intuition about the grimoire is captured by this tree.

One thing you’ll notice about this model, is that it doesn’t characterize speech as a flat line of “this-word-after-that-word-after-this-word.” Rather than a long line of words making up a sentence, this model imagines words as fitting into boxes, which themselves get put into other boxes, and so on, with everything eventually going into the big meta-box, or the sentence.

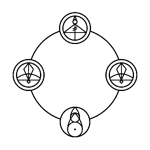

What does this have to do with the magic glyphs of the Boiling Isles? Well, take a look at the four glyphs that Luz knows.

Magic systems re-imagine the fundamental connection between words and things: Words arbitrarily link to things in the primary world...but what if they didn’t? What if words actually caused the things they named? Magic in fiction is based on this what if... and the magic of The Owl House is no different. Except, in The Owl House, it’s the syntactical aspect of language that gets magically emphasized. In other words, for Luz Noceda, magic is composite. You make new magic by combing old magics together according to precise rules. Like any good magic symbol, even inscribing a glyph with the right intention is enough to obtain an explosively obvious result. Plant glyphs summon vines. Fire glyphs summon jets of burning air, and so on, and you get more complex spells by recombining the basic glyphs.

However, as you recall from the embedded video clip above, Just having the glyphs in physical proximity to each other isn’t enough to make a spell work. When Eda tries to violently smoosh a fire and ice glyph together, for example, the result is a faceful of soot. Even though all the right elements for the spell were there, even though Eda’s intention was there, the spell just didn’t go through, because it didn’t have the proper syntax. Eda hadn’t arranged the glyphs circularly like the fastidious Lilith.

And this is the bit that made me eject my breakfast from my oral cavity. It’s so common to representations of magic that it’s easy to miss. But every glyph on the Boiling Isles is cast within a circle. A circle--unlike a line--connotes wholeness, completeness, containment. A line connotes sequence, repetition, invariance. Complex magic spells, being circles within circles--instead of circles in sequence--is exactly the phrasal theory of syntax! Because what is important is not the linear order of the words, but rather their structural relationships. By putting the glyphs on a circle--an infinity of points equidistant from a centre--the magic system of the Boiling Isles eliminates any notions of before or after, and prioritizes atemporal relation. To extend this to language--what is important for a sentence to have its meaning is not that nouns come after determiners, or that adjectives precede nouns, but rather that determiner phrases contain determiners and noun phrases, which contain a noun and may contain an adjective phrase, and so on. It’s containment all the way down.

Even if you don’t need to deploy a full-scale conlang in your world, just thinking about the different aspects of language as they relate to the different aspects of your world, is nevertheless of great utility of the worldbuilder. A rich vocabulary dripping with references to mercs being flatlined while running the net, immediately immerses the reader in a cyberpunk milieu. An unusual sound-system can connote a species’ alienness and otherness with respect to humans, like with my bugs and their mandibular clicks. And the compositionality of language inspired Dana Terrace to imagine a systematic, recombinatory glyph thaumaturgy. As speaking creatures, I contend, we are fascinated with Language. If that fascination doesn’t move you to become a linguist, then it’ll move you to make weirdly wonderful syntactical magic systems.