Brandon Sanderson, author of the celebrated Cosmere collection, recommends, as his favorite, a writing exercise called “The Stranger Rides through Town.” In it, one is prompted to write a short scène for each of four different characters--the stranger, the king, the sheriff, and the professor--as they pass through the same town. This exercise, Sanderson notes--and I agree with him--is excellent practice for developing perspective,for identifying what is essential to a particular character’s viewpoint. The king will necessarily notice different things about the town than the stranger would. He might be struck with the contrast between the bland buildings outside and the gaudy decorations of his palace, might be satisfied or offended by the level of respect he is shown. The stranger on the other hand might be looking for cheap lodging to spend the night, might assume that everyone is going to treat him with disrespect or suspicion. The sheriff will be on the lookout for criminals; while the professor might absent-mindedly commentate on the local dialect, ignoring obvious social cues. Here the link, for you.

I am interested in this exercise because of its takeaway, viz. the same object, the same scène, the same setting or event can be characterized in a multitude of ways, depending on the perspective of a narrator. Perspective refers to one’s individual orientation towards a particular object or event. Are you an observer? A participant? Are you recollecting from memory? One’s perspective can highlight or obscure salient features of an object. Take Hans Holbien’s The Ambassadors for example. The painting was intended to be displayed on a staircase, where viewers would be delighted to see the secret skull appearing and disappearing, as their point of view shifted. Depending on where you’re standing, you’ll get a different version of the painting.

What does all this have to do with grammar? Quite a lot actually. You see, grammar is often taught as a list of restrictions without reason that you have to memorize. I hope that at this point you will realize how silly that view is. Far from being arbitrary, Grammar is the psychological mechanism that allows for speakers to take a point-of-view to begin with. Grammar is the art of perspective.

When you’re writing out a scène, you have the benefit of already speaking your native language, with all of its pre-built perspectives for you to use. Unless you’re some kind of eldritch timeless horror, whatever language you speak is going to be spoken in time and space. I literally mean actual physical time and space. For example, when you’re talking about something that’s about to happen--something in the future--you’re still speaking in the here and now, in what is called utterance time. Your utterance time is the source of your perspective. From your current perspective, you can characterize events as occurring before your utterance (called past tense); during your utterance (called present tense); or after your utterance (called future tense).

Every language will have recourse to a slightly different strategy for encoding these temporal perspectives, and temporality is just one dimension among many that languages can encode. It is important to remember that all human languages share the same fundamental physical and temporal limitations, and so are going to operate with a similar set of spatiotemporal categories. After all, they’re all spoken on earth by mortal beings! However, not all languages are going to “slice the temporal pie,” so to speak, in the same fashion.

For example, words describing activities in French, get a little sub-word, mini-marker suffix--called an inflectional morpheme--to show their temporal status. Look at the examples below. I have put them in bold font. Note that the past tense form cited here is only used nowadays in written French, and has a kinda formal, stuffy feeling. I cite it because it fits the pattern I’m trying to illustrate.

La fille dans-e

The girl dance-(present tense)

The girl dances

La fille dans-era

The girl dance-(future tense)

The girl will dance

La fille dans-a

The girl dance-(past tense)

The girl danced

Samoan, however, has recourse to a different strategy for marking temporality. Rather than modifying the word describing the action with a mini-sub-word-- or morpheme--Samoan has recourse to a whole-ass separate word, that doesn’t have a literal translation--can’t in fact--because it basically means “this happened in the past; this is ongoing; this is finished happening; this is happening now.”

Look at these examples. The format I’m using to illustrate my foreign language examples is a modification of the linguistic gloss. There are three levels of information represented. On the top row, we have the sentence from the language under consideration. On the row below that we have a word-by-word literal translation whose purpose is to illustrate the simple grammatical connections between the words in the first row. And the final row contains an appropriate English translation or paraphrase. I should mention, “prog” stands for progressive and means an activity is ongoing; “prf “ means that the activity is completed; also, “inch” is an abbreviation of inchoative, which I hasten to add is not as complicated as it sounds. It just means “the beginning of an action, as opposed to its end.” English kinda has inchoative-ish words--expressions like “flourish,” “bloom,” or “wind-up.” Samoan is more complex than English, in that regard at least, in as much as it has a systematic way to show that something is just starting.

Sā siva le teine

(past) dance the girl

‘The girl danced.’

'Ole'ā siva le teine

(inch) dance the girl

‘The girl is going to dance.’

'Olo'o siva le teine

(prog) dance the girl

‘The girl is dancing.’

'Ua alu le teine

(perf) go the girl

‘The girl has gone.’

(Mosel & So'o 1997: 21)

https://grambank.clld.org/parameters/GB521#2/21.0/151.9

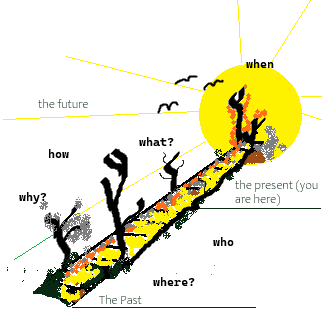

Let’s go back to Sanderson’s “The Stranger Rides through Town”. The driving force behind the exercise, is a process of interrogation. When you’re going through it, describing what the various characters see, you’re forced to perpetually to be asking: Who are they? What are they doing? How are they doing it? Why are they doing it? Where are they going? When are they going?

These questions and the answers that your language makes available could be conceived of existing in perspectival space--or grammatical space, if you will. Here is an imaginative illustration.

The basic idea is that you can picture grammar--or The Grimoire--as an abstract physical space, whose dimensions are described by above question words. Who, why, where, how, what, and so on. In this space, various events are happening, with different numbers of people and things participating, and you have access to every possible perspective for describing them. However, depending on the language you’re speaking, you’re not going to be able to use them all. Different languages will find it important to encode different aspects of a situation.

When using a conlang to build your world, therefore, it is essential for you to keep in mind what temporal perspectives are going to available and why to your people. In my first ever official conlang, for example, I was making a language for a race of beings who had perfected time-travel and perceived time non-linearly. Hence they didn’t characterize events as happening in the past or the future, but instead spoke about what they expected to happen, about what might happen, about whether an event had an endpoint. Your people’s attitudes towards time could be equally reflected in the grammar. Perhaps in a culture where truth is god speaking about the future is taboo, as it is inherently uncertain. These people might use some interesting euphemisms to talk about future events, while not talking about them.

In the next several articles I will continue to develop Grammar as the art of Perspective, and give to you a number of options for expressing your worlds.